The Greek Tragedy

5. Risks of Creditor Countries

Granting credit to Greece entails major risks for other countries in the Eurozone, since they stand to lose part of their claims if the Greek government declares insolvency. Greece has received two bail-out packages to date – as already explained in Section 1 – worth 73.2 billion euros and 142.6 billion euros respectively. The euro countries provided 52.9 billion euros and 130.9 billion euros of the above sums, respectively, the IMF providing the rest. If Greece does not repay its debts, the individual euro countries will be affected according to a specific allocation key, depending on the type of credit granted.

For bilateral credit granted via the first bail-out programme, the 2009 and 2010 ECB capital key for the euro countries excluding Greece initially served as the benchmark. 1 The ECB key was also designated for the second bail-out programme drawing on EFSF funds, this time for the period from January 2011 to June 2013. In reality, however, there were changes to the allocation shares defined initially. Slovakia was not involved at all in the first bail-out programme, which consisted of bilateral credit. Ireland and Portugal dropped out as creditors (after the first and fourth tranche respectively) when they themselves had to apply for bail-out funding from the EFSF and EFSM. This means that Germany, with a 15.7 billion euro share, provided 28.7% of the total bilateral funding of 52.9 billion euros. 2 Similarly, France, with a 11.4 billion euro share, provided 21.5% of the total bilateral funding. The key also had to be adjusted several times for the EFSF funding, due to some countries applying for bail-out funding themselves (Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus) and dropping out as guarantors. Currently Germany is liable for a 29.1% share and France for a 21.9% share. 3 As far as the IMF loans are concerned, by contrast, Germany is only liable for 6.1% and France for 4.5%, in line with their respective capital and voting shares. 4

Germany is liable for 27.1% and France for 20.3% of funding granted via the ESM permanent bail-out fund, but this credit has not been drawn by Greece to date. ESM funding may be used for a third bail-out programme now on the cards, which would still have to be negotiated. That would mean that the protection offered by the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions programme (OMT) – the ECB’s promise to buy unlimited amounts of government bonds of crisis-stricken countries – which has had a lasting interest-lowering effect on government bonds, would also extend to Greek government bonds. Greece is currently not included in this protection.

The liability of other euro countries goes beyond the funding they have supplied. If the Greek government were to declare insolvency, Greek banks would be at serious risk of going bankrupt without further support measures, because they hold a significant volume of their government’s bonds and have received substantial refinancing credit from the Greek central bank only thanks to the Greek government guaranteeing the private bonds that the banks submitted as collateral. Bank insolvencies directly affect all of the Eurosystem’s NCBs, because income from refinancing credit and from the acquisition of securities with self-created money – the so-called seignorage – is pooled among the Eurosystem’s central banks based on the ECB capital key. Insolvencies also indirectly affect the national treasuries that are entitled to receive the seignorage income, and thus ultimately impact national taxpayers.

This state of affairs has been refuted to date with the argument that the Eurozone sovereigns are not obliged to recapitalise their central banks should losses occur. But that is beside the point. Shareholders also lose capital if their company posts losses, although they have no obligation to recapitalise it. 5 If a national central bank charges interest for loaning self-created money to banks in its jurisdiction, or uses that money to acquire interest-bearing securities from those banks, interest is due to all central banks in the Eurosystem on a pro rata basis according to their respective capital shares. National central banks have to pass on the interest to their respective treasuries, where it can be used to finance the national budget. Potential depreciation losses from such loans and securities purchased will be pooled in exactly the same way if the commercial banks or issuers of the bonds acquired by central banks declare insolvency and cannot service their debts. These losses are basically passed on to all national treasuries too. According to the current key, Germany is liable for 25.6% of potential write-offs. France is liable for 20.1%, Italy for 17.5%, and Spain for 12.6%.

The present value (or potential market value) of the seignorage profit distribution from existing loans and assets held by the Eurosystem’s central banks is exactly equal to the central bank money minus the banks’ minimum reserves, because the banks do not have to pay any interest on the latter. At the end of March 2015, this figure totalled 1.259 trillion euros. If potential increases to the monetary base due to inflation and future economic growth are added to this sum, the present value could even be 3 trillion euros. 6 This is the maximum potential liability in terms of the Eurozone's potential seignorage consumption. This sum roughly corresponds to the total annual gross domestic product of the six crisis countries combined, or is slightly more than Germany's GDP (3.230 trillion euros and 2.904 trillion euros, respectively, in 2014).

These statements need to be qualified in view of the fact that the ECB switched money supply in Greece back over to ELA funding in January 2015, as on previous occasions, reaching a volume of 68.5 billion euros at the end of March 2015. ELA funding is formally excluded from joint liability. At first sight, this limits the claim on the seignorage entitlements of the other NCBs.

However, no institution can be liable for more wealth than it actually possesses. This also applies to an NCB, as discussed in Section 3, for such a bank cannot meet its payment obligations to other central banks by printing fresh money, but only by transferring interest income earned from the private sector through permissible money creation, or by transferring equity. In practice, the Greek central bank’s liability is restricted to its liable equity and its share in the interest on the portion of the Eurozone’s monetary base that exceeds the commercial banks' obligatory minimum reserve. Only its entitlement to this part of the interest-revenue pool can be applied to meeting the interest-payment obligations towards the rest of the Eurozone in case the claims derived from national money creation disappear. However, these interest revenues are exactly those that the Greek central bank would have earned if it had not issued an over-proportionate amount of banknotes and an over-proportionate amount of book money that made the net payment orders to other countries possible, and which is measured by the Target balances. The rest of the interest payments, payable to the Greek central bank by the recipients of refinancing credit, are actually due to other central banks, but the Greek central bank would be unable to deliver the corresponding sums to them if Greek commercial banks go bankrupt and the collateral pledged for refinancing credit, or the securities they sold to the Greek central bank, lose their value. The only income that would remain would be the minuscule returns to the Greek central bank's equity capital.

It is conceivable that the Greek government would stand in for the liability instead, but it cannot and doesn’t have to. It cannot because in this scenario the government would be insolvent; and it doesn’t have to do so because the ECB rules do not foresee compulsory calls for capital.

That is why the potential losses of the Eurosystem's remaining central banks extend also to that part of the money supply created in Greece that exceeds its proportionate issuance as defined by Greece's capital share in the Eurosystem by more than the Greek central bank's equity. The potential losses therefore correspond to Greece's total Target liabilities (end of March: 96.4 billion euros) and the liabilities due to its over-proportionate issuance of banknotes (14.0 billion euros), minus the Greek central bank's equity (4.5 billion euros), all of which adds up to 105.9 billion euros.

Germany is liable for 26.3% of this amount, or 27.9 billion euros, while France is liable for 20.7%, or 22.0 billion euros.

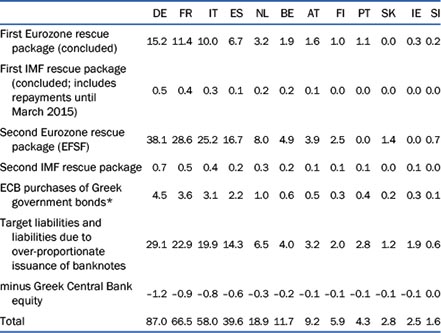

Table 2 offers an overview of the maximum potential losses of selected euro countries if the Greek government were to declare insolvency, which would also affect the commercial banks and the issuers of the securities sold or pledged by those banks to the Greek central bank (in many cases the issuers were the commercial banks themselves).

Table 2: Maximum potential losses of other euro countries if the Greek government and Greek commercial banks declared insolvency and the collateral pledged for refinancing credit loses its value (end of March 2015; billions of euros)

Click on image to enlarge* Greek government bonds acquired by the Eurosystem’s other NCBs as part of the Securities Markets Programme (SMP); own extrapolation of the stock as of the end of 2014.

Note: The shares of individual countries in the individual items of financial assistance are as follows: first Eurozone bail-out package: funding actually granted. First and second IMF packages: share in IMF capital. Second Eurozone package: new contribution key after opting out of Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Cyprus. Capital contribution to ESM: it is assumed here that Greece’s capital contribution accrues to the other contributing countries according to their capital key. Purchases of Greek government bonds by other NCBs, Target liabilities, the over-proportionate issuance of banknotes, as well as the Greek central bank's claims on the Greek banking system: allocation according to the euro countries' respective current capital key in the ECB's equity excluding Greece.

Sources: See Figure 1 as well as IMF, IMF Members' Quotas and Voting Power, and IMF Board of Governors; European Commission, The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece; European Financial Stability Facility, EFSF Investor Presentation; European Stability Mechanism, ESM Treaty, consolidated version following Lithuania's accession to the ESM; European Central Bank, Capital Subscription.

Strictly speaking, these calculations apply to the case whereby Greece remains in the Eurozone despite its bankruptcy and its banks are funded via ELA. Should Greece exit, the situation becomes more complex. Although potential losses from the lost fiscal bail-out funds would be identical, it is unclear how exactly the currency changeover would take place. In all events the commercial relationship between the Greek commercial banks and the ECB, already constrained by the switch to ELA, would be terminated, while the euro-denominated Eurosystem’s Target claim on the Greek NCB would remain as the measure of the refinancing credit given to Greek commercial banks that was used to buy goods, pay off debt or acquire assets abroad. If the Greek central bank were not in a position to settle these claims, the other central banks would share in the losses according to the ECB capital key, as shown in Table 2.

But what happens to the euro banknotes and the commercial banks' accounts with the Greek central bank in this case? If they are redenominated into drachma, the other countries will not suffer from a loss in refinancing claims resulting from the original act of issuing the euro banknotes. From this point of view, Greece's exit would be cheaper for the community, quite apart from the fact that an exit would presumably avoid a steadily rising flow of bail-out funds – and thus even greater losses in the long run.

However, if the euro banknotes were not exchanged into drachma, but remained in the hands of the Greek population, in effect representing a parallel currency, a loss would be sustained by the rest of the Eurosystem inasmuch as these banknotes would be crowded out within Greece by the new drachma banknotes and be used for purchases in the rest of the Eurozone. This would entail losses related to goods that in effect "disappear" from the rest of the Eurozone or, equivalently, losses in terms of a reduction in the potential for money creation via refinancing credit to commercial banks in the remaining Eurozone and, with it, the corresponding interest income. Euro banknotes that permanently circulate in Greece, on the contrary, would not per se lead to losses for the Eurosystem.

Continue to Section 6: Loss of Competitiveness and Four Options for Greece

Footnotes

1 The ECB capital key is, in principle, defined as a simple average of the population and GDP share of each euro country.

2 See European Commission, The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, p. 6.

3 See European Financial Stability Facility, EFSF Investor Presentation, p. 31.

4 See IMF, IMF Members' Quotas and Voting Power, and IMF Board of Governors

5 See H.-W. Sinn, The Euro Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets, and Beliefs, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, especially Chapter 1, in the section entitled: "The European Central Bank", as well as Chapter 8, in the section entitled: "No Risk to Taxpayers?". See also H.-W. Sinn, "The Eurosystem Is Like a Corporation", Der Tagesspiegel, 11 February 2015, p. 16; and H.-W. Sinn, "The ECB's Money Does Not Fall Like Manna from Heaven", Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 15 March 2015.

6 See W. Buiter and E. Rahbari, "Looking into the Deep Pockets of the ECB," Citi Economics, Global Economics View, 27 February 2012, http://blogs.r.ftdata.co.uk/money-supply/files/2012/02/citi-Looking-into-the-Deep-Pockets-of-the-ECB.pdf. The figure cited there of 3.4 trillion euros was reduced by the Eurosystem equity (including balancing items from revaluation) of 411 billion euros at that time. See European Central Bank, Annual Report 2010, Frankfurt am Main, p. 269.