The Greek Tragedy

4. Interest Rebates

Greece was not only assisted with public sector loans worth 325 billion euros, equivalent to 182% of its GDP. It also enjoyed significant interest rebates on loans that had been granted by international institutions. In autumn 2012 the interest rates on the bilateral loans granted by the euro countries as part of the first bail-out programme were lowered by one percentage point, at the same time extending their maturity by 15 years to 2041. The maturity of the EFSF loan was also extended by 15 years, and interest payment was deferred for 10 years. In addition, fees on the EFSF loan were reduced. In present value terms, these measures were equivalent to a once-and-for-all haircut of 43 billion euros. 1

Moreover, in spring 2012 Greece negotiated a debt restructuring (i.e. a haircut) of all of Greek government bonds that was worth a total of 105 billion euros, 2 marking a historically unprecedented level of debt relief. This can undoubtedly be referred to as a sovereign insolvency, since a haircut is the main characteristic of such an occurrence, even if the definition of sovereign insolvency remains nebulous: it is not defined by commercial law, nor is there any court to adjudicate it.

At interest rates of around 4.6% at the time that the bonds were written off, the 105 billion euros in debt relief corresponds to lasting budget relief equalling around 2.5% of GDP. 3 Moreover, it is worth noting that the haircut only partially represented debt relief granted to Greece by foreigners, since the government’s creditors also included Greek banks and Greek investors. Greece also benefited from the fact that interest on its Target overdraft credit was only charged at the ECB’s main refinancing rate, which currently is only 0.05%.

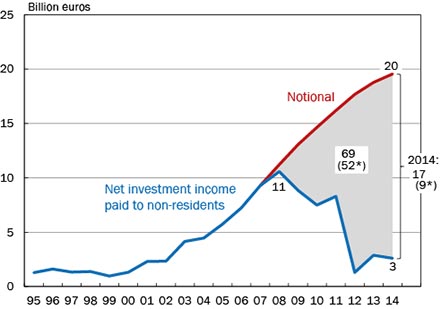

Figure 8 shows the overall debt relief effects of the interest rate reductions. The blue curve shows investment income flowing abroad that Greece was paying to foreign investors net of the income Greek investors earned abroad. Let us call this income 'interest income' for simplicity, alluding to a very broad definition of the term, as all sorts of cross-border capital income are included. As the chart shows, Greece’s interest burden of around two billion euros in the year that it joined the euro (2001) soared to 11 billion euros in the crisis year of 2008, but subsequently fell to just 3 billion euros by 2014. While the increase was to be expected in view of the huge Greek current-account deficit (as shown in the previous section) and the corresponding increase in foreign debt, the post-2008 decline was remarkable given that Greece continued to have current account deficits up to 2012 and given that, as shown in Figure 6, the market interest rates for Greek government bonds during the crisis were consistently higher than in the years after it joined the euro in 2001, continuing to soar until 2012. Against this backdrop, Greece’s interest burden should really have been expected to explode rather than decline after 2008.

Figure 8: Greece’s interest gains

Click on image to enlarge* In real terms

Key: The notional yardstick values used for the comparison are calculated on the basis of the 2007 overall rate of interest for Greece, defined as the ratio between the actual net investment income Greece paid to foreigners in that year (9.32 billion euros) and the country’s net foreign debt (negative net investment position) at the beginning of the year (178.2 billion euros). This interest rate was 5.2%. In a first (nominal) variant of the notional yardstick calculation, the thus-defined 2007 rate of interest was applied to the fictitious net foreign debt that in the following years would have resulted from an accumulation of current-account deficits. Account was taken of the fact that in the hypothetical case of constant interest rates the current account deficits themselves would have been larger than they actually were, given that net interest payments to foreigners are part of the current-account deficits. Alternatively, a variant of the notional yardstick calculations was carried out where the 2007 real rate of interest was kept constant, the real rate of interest being defined as the nominal rate minus the annual rate of increase in the harmonised consumer price index for the Eurozone. The numbers in brackets give the respective results. Note that balance-of-payments statistics as of 2014 are calculated internationally according to a new method (Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition: BPM6). Since the results for Greece according to the new system are only available as of 2009, data produced on the basis of the old standard are used up to and including 2008. Preliminary calculations showed that this had only a negligible impact on the results.

Source: Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, Balance of Payments – International Transactions (BOP) (up to 2008); Eurostat, Economy and Finance, Balance of Payments – International Transactions (BPM6) (as of 2009).

The main explanation for this phenomenon is presumably that Greece did not pay market interest rates, as a result of the three effects cited, namely the interest rebate on fiscal credit, the low interest on the Greek central bank’s refinancing credit and the interest saved thanks to the haircut. In addition, the fact that the subsidiaries of foreign companies present in Greece transferred lower profits to their parent companies may also have contributed to the decline in net investment income, for net investment income is broadly defined and covers all types of cross-border capital revenues.

The red curve featured in Figure 8 represents an attempt to assess the interest advantage enjoyed by Greece thanks to the overall combined effects cited above. It shows a notional net interest burden that would have occurred if Greece had been obliged to continue to pay the average interest rate that it actually paid in 2007, prior to the outbreak of the crisis. There is clearly a growing gap between this notional burden and the actual burden. For the period 2008 to 2014 the gap adds up to 69 billion euros, as shown by the shaded area. This sum gives a rough guide to the interest advantage gained by Greece during the first seven years of the crisis thanks to low interest rates, interest rebates and debt relief.

The lower interest rate enjoyed by Greece made a major contribution to the improvement in the Greek current-account in its own right. In the period from 2007 to 2014 the Greek current-account improved from -32.6 billion euros to +1.6 billion euros. Under the same conditions, and if the interest rate had remained as high as in 2007, the 2014 deficit would have been -15.4 billion euros.

However, Greece's current account deficit would presumably have been even larger if the country had been forced to borrow from the markets, as at least for Greek government bonds (cf. Figure 6) market rates were higher than in 2007 throughout the entire crisis, despite the fact that the international community's financial protection measures reduced market interest rates significantly as of 2012 by acting as free insurance for investors. In this sense, using the 2007 actual overall interest rate as a benchmark leads to an underestimation of the gains that the Greek economy obtained from the interest reductions. While the above calculations are carried out in nominal terms, an alternative calculation (shown in brackets in the figure) takes into account that some of the interest decline may have resulted from the slight decline in the Eurozone inflation rate that took place over the period. Adjusting for this effect, Greece’s interest savings over the seven years from 2008 to 2014 shrink from 69 billion euros to 52 billion euros. Savings in 2014 shrink from 17 to 9 billion euros.

Continue to Section 5: Risks of Creditor Countries

Footnotes

1 The Ifo Institute initially estimated the cash value at 47 billion euros, cf. "Bailing out Greece Means Haircuts Totaling 47 Billion Euros at the Expense of Public Creditors", Ifo press release, 30 November 2012. When the exact repayment conditions for the debt became known at a later date, this value was adjusted downward by 4 billion euros. Cf. "Further Relief Planned on Bailout Loans to Greece", Ifo press release, 11 February 2014.

2 Bonds worth a total of 205.6 billion euros were offered for exchange, of which 95.7% were actually exchanged (cf. European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs, Financial Assistance in EU Member States, Greece, available here. The haircut totalled 53.5%, which equals debt relief 105.3 billion euros.

3 Calculated on the basis of the average interest rates paid by the Greek government on all outstanding debts.