The Greek Tragedy

3. Who Benefited from the Rescue Credit?

Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis recently asserted that 90% of the public credit given to Greece had been used to serve private credit granted by international lenders; in other words, to rescue, amongst others, European banks. 1 The financial support practically never reached the Greek citizenry at all. The Greek population, goes the argument, is suffering under the austerity policy imposed by the Troika, which has brought about a humanitarian catastrophe. Other economists have also criticised the austerity policy allegedly imposed by the euro

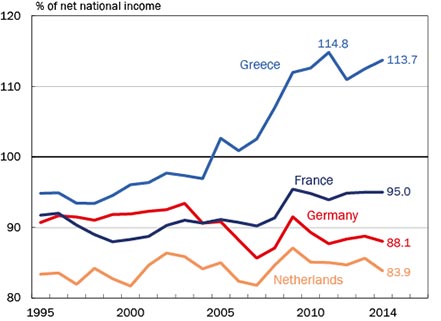

It is easy to see how these assertions miss the point just by considering the relationship between Greek public and private consumption on the one hand, and net national income on the other, as shown in Figure 5. While the ratio in countries like Germany, France or the Netherlands, to take just three examples, hovered around 90%, in Greece it climbed from around 95% in the years following adoption of the euro to more than 110%, where it has stayed until now. In 2014, aggregate consumption reached 113.7% of net national income, by far the highest value of all euro countries. In view of the fact that an economy normally cannot consume more than its net national income without running its reserves to the ground, this remarkable development can hardly be reconciled with the "humanitarian catastrophe" thesis.

Figure 5: Public and private consumption relative to net national income

Click on image to enlargeSource: Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (including GDP), GDP and Main Components – Current Prices, Final Consumption Expenditures; and Income, Saving and Net Lending/ Borrowing, Gross National Income at Market Prices; European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs, Economic Databases and Indicators, AMECO – the annual macro-economic database, National Income.

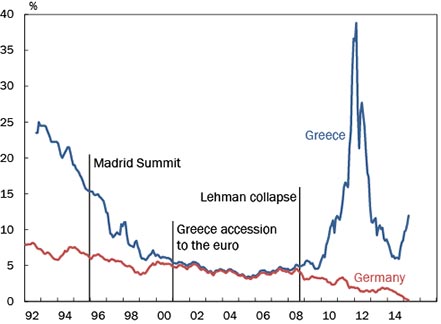

The fundamental factor behind the exploding consumption was the lower interest rates that Greece’s adoption of the euro brought about. Yields on Greek government bonds, as shown in Figure 6, fell from about 25% to 5%. A similar development occurred in the private sector. As Box 2 explains, the lowering of interest rates was spurred by regulatory errors and by the implicit protection expected by investors from the Eurosystem. While the lower rates meant that private and public debtors had to pay less interest to foreign creditors, which increased the net national income and hence, taken by itself, reduced the consumption excess, this was more than offset by the increase in borrowing, which swelled the consumption excess further. The low interest rates made it tempting to improve the living standard by borrowing more abroad, since the sustainability of the additional indebtedness appeared to be assured. As a result, Greece's foreign debt jumped from the time of euro introduction (2001) to the pre-crisis year 2007 from 68 billion euros to 214 billion euros, 4 while the net-foreign-debt/GDP ratio more than doubled, from 45% to 92%.

The public sector was not the main factor behind this development, since it increased its debt-to-GDP ratio only from 105% to 107% over the same period. 5 The government can only be reproached for not using the enormous advantage brought about by the lower interest rates on the outstanding government bonds – worth about 7 percentage points of GDP if compared to the year of the Madrid summit (1995), in which the timing for the euro was finally decided – for paying back debt, but to increase expenditures instead. 6 It raised the salaries of public employees and hired ever larger numbers of them. The increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio was in fact due primarily to higher private sector borrowing for consumption purposes and also for investment in construction. The credit-financed expenditures, combined with the savings from lower interest payments, made it possible for Greek wages to rise, from the euro adoption in 2001 to the onset of the crisis in 2007, by 65%, 7 while Greek GDP rose only by a nominal 53% and a real 28%. 8 Note that the true discrepancy between the rise in wages and the improvement in economic performance must have been even higher that what these figures suggest, because in the national accounts GDP consists in part of the salaries of public employees and therefore rises automatically when salaries are increased. Furthermore, wage increases may give the domestic sectors of an economy a boost by stimulating consumption demand despite the fact that they undermine external competitiveness. Seen in this light, a credit-financed upturn in domestic demand leads to an underestimation of the disadvantageous developments described above.

Figure 6: Effective yield of 10-year government bonds

Click on image to enlargeSource: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Germany: BDBRYLD, Greece GRBRYLD (as from 04/1999) GRESEFIGR (as from 01/1996) GRESEFIGR (Data last accessed on 10 February 2014; since 09/1992).

BOX 2

Causes of the interest rate drop

Before Greece joined the euro, investors demanded high yields for Greek government bonds because they had to price in the risk of being repaid in depreciated drachmas. As Greece approached the moment of euro adoption, this risk gradually diminished, the interest spreads declining accordingly until they practically disappeared when the moment of adoption came.

It is not clear when the shrinking of Greek spreads began, because the statistical information for Greece goes only back to 1993. That notwithstanding, December 1995 marks an important milestone, namely the formal decision reached at the Madrid Summit to introduce the euro as a virtual currency already in 1999, so that at the latest at that time no further exchange rate uncertainty occurred among the participating countries. While at the time it was not known when Greece would eventually join in, the intensive negotiations led investors to expect a speedy accession, so that the trend towards lower spreads was at least reinforced.

The risk of sovereign default, which would have also justified charging an interest premium for Greek government bonds, was evidently deemed insignificant by investors. This proved to be wrong with hindsight, as evidenced by the haircut applied to Greek debt in 2012. Still, it was not implausible, because investors could rightly expect fresh liquidity to be made available to the Greek financial system at all times, in order for banks to buy back debt or for the state to obtain follow-on financing. Rightly as well, they could expect euro membership to afford them exit options if the need should arise, since they were well aware of the possibility of the Greek central bank propping up the banks in its jurisdiction with emergency credit, if and whenever needed. Where they miscalculated was with regard to the size of the Greek shortfall, because it exceeded what the other countries and the ECB were ready to bear.

The willingness to lend relinquishing practically all premium was also encouraged by the Basel system of bank regulation, which allowed banks to set aside no capital reserves for government bonds if they documented their risks in accordance with the so-called standard approach, which is based on predetermined risk weight categories. On top of this, the EU also gave its banks the possibility, quite at odds with the Basel rules, to even set aside no capital reserves if they calculated their risks according to their own risk models. The banks could thus pick out the advantageous elements from two risk assessment approaches. 9 Since bankers often optimise only for the short term, and in making their decisions pay closer attention only to the risks arising during their tenure, it is no surprise that they were ready to lend to Greece at minimum premia if the supervisory bodies did not forbid such a practice and, on the contrary, actively encouraged it. Who could accuse bankers of having acted recklessly when they actually were operating in compliance with prevailing regulation and when the supervisory bodies themselves indicated that, in their opinion, Greek government bonds were risk-free?

Not only bank managers, but also managers of insurance companies aimed for short-term profits, since the Solvency Regulation that they had to comply with demanded no capital buffers for purchases of Greek sovereign bonds or of those of other euro countries. Seen in this light, the convergence of interest rates that encouraged Greeks to live above their means can be laid at the feet also of the executives of the financial institutions and the politicians who set up deficient regulatory systems. It is too simple and unfair to blame only Greece.

It is remarkable that the excess of consumption over income kept increasing even after the onset of the global financial crisis, which engulfed Greece as well. This was not only the result of a deliberate attempt to keep the consumption level unchanged even after the economy started to wobble, but also because wages were further increased with more debt, despite the on-going crisis. The salaries of Greek public employees rose by around 19% in 2008 and 2009, although Greece’s GDP rose only by 2% in nominal terms and shrank by 5% in real terms over these two years. 10 It was only later that the upward trend was broken and wages started to come down.

In view of the fact that since 2008 Greece could only borrow in the capital markets paying exorbitant premia, one may wonder where it got the money to finance its consumption overhang. The answer lies with the credit from the local money-printing press discussed in Section 1. Once the ECB Council allowed it by dramatically lowering the collateral requirements, the Greek central bank lent increasing amounts of freshly created money to the banks in its jurisdiction, which they in turn used to buy Greek government bonds and to lend to the private sector. The government used the money to increase the salaries of public employees, although the economy was sagging, the rising salaries leading then to higher consumption. Private individuals also took bank loans to finance their high consumption standards. The bloated consumption manifested itself in net payment orders to other countries aimed at purchasing goods abroad which, as discussed in Section 1, are measured by the Target balances together with the payment orders to redeem private debt and acquire assets abroad (see Fig. 1).

Greece financed itself with Target credit only in the initial phase. After the ECB spearheaded the rescue, the parliaments of the Eurozone countries had no other option but to provide follow-on financing by means of fiscal rescue credit. The credit pre-financed, and thus forced, by the Greek central bank made it possible to keep consumption above 100% of income, despite the fact that Greece had been largely shut out of the international capital markets since 2008.

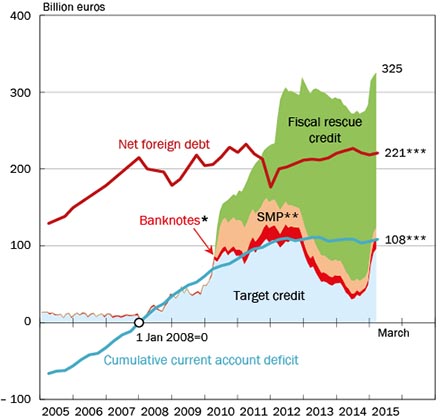

Public credit did not flow solely into consumption; because it allowed Greek citizens and banks to redeem their private debt, it also helped investors and asset owners who otherwise might not have seen again the money that they had lent to Greece. Yanis Varoufakis is thus right, although he grossly errs regarding the magnitude. This is shown in Figure 7. The chart repeats the information of Figure 1, but is now complemented with the blue curve that depicts Greece’s cumulative current-account deficits, and by the red curve, which depicts its net foreign debt (negative international investment position). 11

Figure 7: Public credit, cumulative current account deficits, and foreign debt

Click on image to enlarge* Liabilities of the Greek central bank to the Eurosystem due to over-proportionate banknote issuance.

** Greek government bonds bought by other Eurosystem NCBs within the framework of the Securities Markets Programme (SMP) minus the government bonds of other countries bought by the Greek central bank under the SMP.

*** Estimate: January to March 2015.

Sources: See Figure 1, and also: Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, Balance of Payments – International Transactions; Ifo Institute estimates.

Let us first consider the curve depicting the cumulative current-account deficits. A current-account deficit is essentially an excess of imports and net interest payments to other countries, over exports and transfer receipts (such as guest-worker remittances or EU funds). The deficit is identical to the capital imports of a country, which occur through net borrowing from private and public creditors and net sales of assets to foreigners. The net borrowing from public creditors can take the form, for example, of fiscal rescue credit, or of a Target credit between Eurosystem NCBs.

The slope of the blue curve shows the current-account deficit before and after the early-2008 reference point, which by definition has a level of zero. The level of the curve depicts the sum of the deficits calculated at each observation point since the reference point. In the negative area, the distance of the cumulative current-account deficit curve from the zero axis depicts the sums of current-account deficits from the respective point in time until the start of 2008.

The chart makes abundantly clear that the current-account deficits were financed before 2008 with private capital imports, because the Target curve runs flat close to the zero axis, and that from early 2008 to early 2010 they were financed practically in their entirety by Target credit, that is, by an additional creation of money by the Greek central bank beyond the domestic liquidity needs of the Greek economy. Private capital imports dwindled practically to nought during this period. It is not quite clear why this was so. It could be that international lenders avoided Greece and the ECB stepped into the breach. It may also be that Greek debtors refrained from borrowing from foreign lenders because the ECB allowed the Greek central bank to provide credit to the banks in its jurisdiction at cheaper rates than the increasingly nervous investors did. The public-employee salary raises in 2008 and 2009 mentioned above, together with the fact that the annual current account deficits did not come down (measured by the slope of the cumulative current account deficit curve), show that the credit provided by the Greek central bank with freshly created money was generous enough to make up for the dearth of private foreign credit.

Before 2008 Target credit played no role at all, because the ECB had pursued a restrictive monetary policy that ruled out an asymmetrical expansion of the monetary base to the benefit of individual countries. Target credit was only seen as a temporary overdraft facility of the Eurosystem that was to be settled through restrictive local money creation, so that the market participants were forced to turn directly, or indirectly through their banks, to foreign lenders when they needed credit in excess of domestic savings. 12

Since the rise in Greek Target liabilities in the years 2008 and 2009 was very nearly the same as the rise in Greece’s cumulative current account deficit, on balance during these two years no public foreign credit was used to repay foreign investors. The portion of the public credit used for repaying private foreign loans, and which Yanis Varoufakis refers to in his statement, was therefore practically zero during this period. All public credit came from the ECB system, and it was used over these two years practically exclusively to finance the Greek current account deficits, and thus served to support and further raise the Greek living standard. The Greek central bank lent out the freshly created money to the commercial banks, and these in turn lent it out to private individuals and to the government. The private individuals financed thus their consumption and investment goods, which partly came from abroad, and the government financed public employee salaries and other expenditures. The salary-earners and other recipients of state resources used the money to buy imported goods. This is a simplified, but essentially accurate outline of what transpired during the first two years of the crisis.

The situation changed dramatically when the Eurosystem NCBs started to asymmetrically purchase government bonds in 2010 (SMP) and the community of euro member states deployed the rescue packages, since now the overall sum of public credit grew beyond the cumulative current account deficits. While part of the fiscal funds were manifestly used from 2013 to replace the refinancing credit given by the Greek central bank to the commercial banks, and thus retroactively finance the current-account deficits of the previous years, as evidenced by the retreat of Greek Target liabilities, the other portion – the one above the blue curve depicting the cumulative current account deficits – was used to replace fleeing capital and, thus, to make capital flight possible in the first place.

A substantial portion of the capital flight was caused by foreign investors, primarily French and also German banks, who refused to roll over their loans when they reached maturity, as they had done previously. 13 But Greek investors also brought their money abroad, by selling assets to the domestic banks or taking out loans from them and bringing abroad the liquidity thus obtained.

At the end of March 2015, the sum of current account deficits accumulated since early 2008 was 108 billion euros, equivalent to one-third of the multilateral and intergovernmental loans provided to Greece, which amounted to 325 billion euros. Two-thirds of the public credit was thus apparently used to finance capital flight and one-third to finance the current account deficit – ultimately the living standard that could no longer be financed with the income of the Greek citizenry. Thus, over the entire crisis period it can hardly be argued that barely 10 percent of the public credit benefited the Greek people, as Finance Minister Varoufakis does. Apart from the above, Greek debtors benefited from the fact that the international community helped them meet their obligations towards foreign creditors, and also made it possible for them to bring their wealth out of the country.

The red curve, which depicts Greece's overall net foreign debt, which currently stands at 221 billion euros, shows as well which portion the public funds received by Greece from the international community, on balance, went to capital flight and which to repayment of foreign debt. If the sum of public credits lay below this value, on balance there would still be some private foreign investor exposure to Greece. However, at 325 billion euros, it lies around 100 billion euros above Greece's net foreign debt. This is only possible if Greek investors, on balance, own 100 billion euros more worth of assets abroad than foreigners own assets in Greece. Thus, roughly speaking, it can be said that out of the public credit received during the crisis years, one-third was used to finance the current account deficit, one-third to repay Greek foreign debt, and one-third to bring Greek citizens' wealth abroad.

There is ample anecdotal evidence of the latter. For years now, Greek investors have played a large, and much debated, role in the London and Berlin property markets. 14 And during the current flare-up of the Greek crisis, numerous newspaper articles report of Greeks raiding their bank accounts to bring their money abroad. The strong recent jump in Greek Target liabilities shown in Figure 6 is quite likely due to capital flight by Greek citizens and institutions borrowing in the local banking market to acquire assets abroad. The foreign assets owned by Greeks ought to be kept in mind in any discussion of haircuts on Greek government and central bank debt in case of an eventual Greek exit from the euro.

The current wave of capital flight was made possible by the ELA credit discussed in Section 1, that is, emergency credit that the Greek central bank gave to Greek commercial banks. By late March 2015, the Greek central bank had given its commercial banks 68.5 billion euros in ELA credit, 15 and this sum continued to grow afterwards as well. By mid-May it had reached 80 billion euros, according to press reports. 16 Without ELA credit the capital flight would not have been possible, because it requires a payment order to a foreign bank which, in turn, implies removing central bank money within Greece and creating an equivalent amount of such money in the recipient country. If the liquidity removed from Greece were not replenished through ELA credit, the commercial banks would quickly face a liquidity squeeze which could only be averted by setting up capital controls to stop the payment orders.

The ECB communications regarding ELA give the impression that the ECB has allowed Greece to issue such credit. This is but half the truth, since, as discussed in Section 1, ELA credit must not be authorised but only announced. It is the Greek central bank itself which allows this credit in its jurisdiction, not the ECB Council. The latter can only block the granting of such credit with a two-thirds majority, and when it fails to do so, ELA credit is legal. By financing and making possible the capital flight, the Greek central bank forces the other Eurosystem NCBs to grant it Target overdraft credit, since these NCBs must honour the payment orders to the benefit of Greek citizens; in other words, they must create money without getting a claim on the commercial banks in their jurisdiction, as is normally the case. These claims have already been made against the Greek commercial banks.

Formally, ELA credit is given at the risk of the Greek central bank, as explained previously. If the recipient commercial banks should go bankrupt and the collateral lose its value, the other euro NCBs will not share the burden represented by the permanent loss of interest income from the credit being written off. In fact, the fiction remains that the Greek central bank will continue to pay the interest to the rest of the Eurosystem. This is unrealistic in the face of the sums mentioned, since the capital of the Greek central bank as of 31 March 2015, including valuation reserves, amounted to barely 4.5 billion euros, plus an ownership-equivalent share in the interest-bearing part of the Eurosystem's monetary base (stock of central bank money minus minimum reserve) amounting to 36.5 billion euros. As a result, its potential liability to the rest of the Eurosystem amounts ultimately to 41 billion euros. Thus, out of the 68.5 billion euros in ELA credit given by the end of March, 27.5 billion euros imply, contrary to the legal fiction, a liability assumed by the other Eurozone NCBs. 17

Each euro in additional ELA credit that the Greek NCB creates today and lends through the banks to someone intent on capital flight, who then cables the money to another euro country, is a credit given by the respective foreign NCB to the Greek one, since the former has to issue central bank money to honour the payment order to a bank in its jurisdiction on behalf of the Greek central bank. While private Greek capital flees abroad, public credit flows to Greece in the form of Eurosystem credit. It is simply not possible for the Greek central bank to bear the entire liability for this credit should the commercial banks in its jurisdiction go bankrupt and the collateral pledged lose its value. The liability lies in reality with the other Eurosystem NCBs, in proportion to their respective capital keys.

The ECB itself assumes in its calculations of the liability framework that liability derived from ELA credit only applies to the portion that is not collateralised, while it applies deductions to the collateral pledged according to its own rules. In this way, it props up the fiction that even the 80 billion in ELA credit given by mid-May 2015 is secure. However, the collateral consists largely of government bonds and state-guaranteed bank bonds, which derive their safety from a state that the Greek Finance Minister himself has described as insolvent. 18

Continue to Section 4: Interest Rebates

Footnotes

1 See Y. Varoufakis, "Schluss mit Schwarzer Peter", Handelsblatt, 30 March 2015, p. 48.

2 See M. Fratzscher, "Fünf Thesen, fünf Irrtümer: Targetsalden", Handelsblatt, 16/17/18 January 2015, p. 53, as well as P. De Grauwe, "The Creditor Nations Rule in the Eurozone", in: S. Tilford und P. Whyte, The Future of Europe's Economy – Disaster or Deliverance?, Centre for European Reform, London, p. 11–23.

3 See D. Dittmer, "Jahrelange Insolvenzverschleppung? Die Horror-Bilanz der Griechenland-Hilfen", n-tv, 13 March 2015.

4 See Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, Balance of Payments – International Transactions (bop), International Investment Positions – Annual Data.

5 See European Commission, General Government Data, Part I, Spring 2014, p. 33. These data were prepared in accordance with the former system of National Accounts (ESVG 95). Data under the new system (ESVG 2010) only includes Greek indebtedness from the period 2011 until 2014.

6 In 1995, Greece devoted 11.3% of GDP to paying interest; in 2007 only 4.5%. See European Commission, ibid., p. 31.

7 Sum of workers' income; see Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESVG 2010), Annual Accounts, Main GDP Aggregates.

8 See Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESVG 2010), Annual Accounts.

9 Regulation Governing the Capital Adequacy of Institutions, Groups of Institutions and Financial Holding Groups, Para. 26 No. 2 littera b in conjunction with Para. 70 section 1 littera c; Directive 2006/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 Relating to the Taking Up and Pursuit of the Business of Credit Institutions (Recast), Para. 80 No. 1 in conjunction with Para. 89 No. 1 littera d. As far as it is known, many euro countries integrated these regulations into national laws. Germany, for example, did it with the directive regarding the adequacy of capital requirements of Institutes, Groups of Institutes and Financial Holdings, Para. 26 No. 2 littera b in conjunction with Para. 70 No. 1 littera c; Directive 2006/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions (recast), Para. 80 No. 1 in conjunction with Para- 89 No. 1 littera d.

10 See Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESVG 2010), Annual Accounts, Detailed breakdown of main GDP aggregates.

11 It must be pointed out that since 2014 the current account statistics are prepared according to a new methodology (Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition: BPM6). Since the results for Greece with the new system are available only from 2009 onwards, data calculated with the old standard is used for the years up to 2008. A comparison of the overlapping data points show that this had only a negligible effect on data.

12 See H. Schlesinger, "Die Zahlungsbilanz sagt es uns", ifo Schnelldienst 64 (16), 2011, p. 9–11.

13 See Bank for International Settlements, Statistics, Consolidated Banking Statistics, and H.-W. Sinn, The Euro Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets, and Beliefs, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, in particular Chapter 5: "The White Knight", Section "The Crash".

14 See Focus Online, "Reiche Griechen fliehen nach London", 4 November 2011, as well as faz.net, "Reiche Griechen kaufen Wohnungen in Berlin", 17 December 2012

15 Since ELA credit is not shown directly in the Greek central bank's balance sheet, the position "Other claims on euro area credit institutions denominated in euro" will be used here as an approximate value.

16 See "EZB erhöht Ela-Notkredite für Griechenland um 200 Millionen Euro", faz.net, 20 May 2015.

17 See H.-W. Sinn, The Euro Trap, op. cit., in particular Chapter 5: "The White Knight", Section "ELA Credit"; See also H.-W. Sinn, "Die EZB betreibt Konkursverschleppung", Süddeutsche Zeitung, 10 February 2015, p. 18. An abridged version was published as: "Impose Capital Controls in Greece or Repeat the Costly Mistake of Cyprus", Financial Times, 16 February 2015.

18 "The disease that we're facing in Greece at the moment is that a problem of insolvency for five years has been dealt with as a problem of liquidity." Y. Varoufakis, "Greek finance minister: 'It's not about who will blink first'", BBC Newsnight, 31 January 2015.