The Greek Tragedy

2. Did the Money Help?

Given the truly gigantic rescue credit provided to Greece, which at a net 325 billion euros has turned out to be more than three times larger than originally calculated by the European Commission and the IMF for the first rescue package (110 billion euros), 1 one could be excused for thinking that Greece’s economy must be on the mend. After all, the EU countries were of one mind that the package served to buy time for the Greek economy to reform and to provide Greece help to help itself.2 Furthermore, the German Chancellor stressed time and again that the rescue programme would not be extended. 3

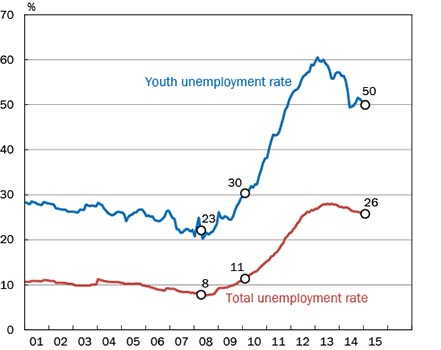

The reality is sobering. As Figure 2 shows, Greece's unemployment more than doubled from 11% in the first quarter of 2010, when the first Grexit debate took place, to 26% in the first quarter of 2015. 4 Youth unemployment, in turn, rose from 30% to 50%. Every second Greek youth between 15 and 25 years of age who is not attending school or university is unemployed. If this situation does not improve fundamentally soon, an entire generation of Greeks will be lost to the labour market.

Figure 2: The evolution of unemployment in Greece

Click on image to enlargeSource: Eurostat, Database, Population and Social Conditions, Labour Market, Employment and Unemployment.

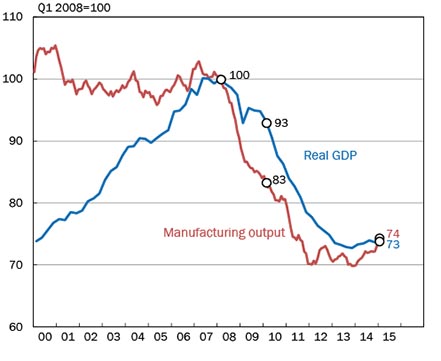

The evolution of the Greek economy as a whole can also be described only as catastrophic. As Figure 3 shows, Greece’s industrial production had fallen by 26% by the first quarter of 2015 compared to its pre-crisis level (first quarter 2008), and GDP by 27%.

Figure 3: The Greek economic slump

Click on image to enlargeSources: Eurostat, Database, Industry, Trade and Services, Short-term business statistics, Industry; same institution, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESA 2010), Quarterly Accounts, Main GDP aggregates; same institution, Press release 84/2015, Flash estimate for the first quarter of 2015, 13 May 2015; Production: Moving 5-month average.

Although the bulk of the slump occurred before fiscal rescue credit was provided, the support given shows no discernible positive effects. Real GDP fell between the first quarter of 2010 and the first quarter of 2015 by a further 21%, while manufacturing output dropped by another 10%.

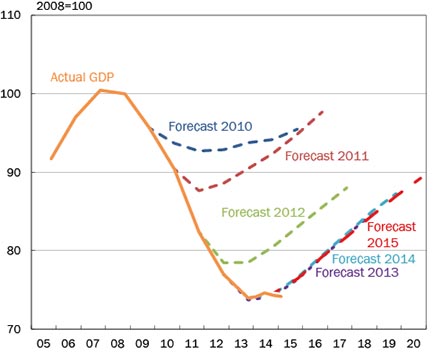

As Figure 4 shows, the evolution of the economy came nowhere close to the IMF expectations and forecasts. The IMF, which took part in the rescue, turned out to be too optimistic. The fact that this was purely calculated optimism, aimed at establishing the sustainability of Greek debt required for the continuance of rescue credit for the country, was admitted and criticised by IMF representatives in June 2013. 5

Figure 4: Greece's Real GDP: Comparison of the real evolutiona) with the IMFb) forecasts

Click on image to enlargeActual evolution from 2005 until first quarter 2015 and comparison with the IMF spring forecasts from 2010 to 2015.

a) Actual GDP; 2005 – 2013, yearly data; quarterly data starting first quarter 2014. Status: May 2015.

b) Respective spring forecasts.

Sources: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, April 2010 to April 2015; Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESA 2010), Quarterly Accounts, Main GDP aggregates; same institution, Press release 84/2015, Flash estimate for the first quarter of 2015, 13 May 2015.

The chart above gives the impression that, after the failure of the first forecasts, better forecasts were made starting in 2013. The economy did indeed pick up in 2013 and 2014, as Figure 3 shows. However, in view of the latest Greek crisis, which has led to a new recession in the past two quarters, these forecasts will likely also turn out to be too optimistic.

Whatever the case, it seems that the money has not helped. It did provide a Keynesian boost to domestic demand, as is always the case when the government carries out credit-financed spending programmes, and which could explain the light improvement of 2014. But signs of a sustainable recovery of the Greek economy are entirely lacking.

This may be due to the fact that the reforms demanded of Greece by the Troika as condition for granting rescue credit have either been barely carried out or not at all. While there have been pension cuts and modest tax increases, pensions are on average still considerably higher than in

Already back in 2013 doubts were voiced that Greece would tackle the promised reforms seriously. 11 An assessment of 787 conditions that the Troika conducted found that not even half had been fulfilled. The Greek government was still working on 76 of them, and no effort to introduce measures to fulfil 357 other conditions could be observed. 12 Practically no progress was made on privatisation either. On 2 July 2011, Greece had committed to sell 50 billion euros worth of state property in order to be able to meet its credit obligations. 13 But by December 2014, privatisation proceeds amounted to barely 3.1 billion euros. 14

The sale of harbour facilities in Piraeus to a group of Chinese investors was stopped by the new government led by Alexis Tsipras: the election campaign of his party Syriza was based on an open rejection of the reform commitments made with the Troika. The attempts to bring the government around have proved fruitless up to this writing (May 2015).

At first sight, it may seem puzzling that Greece's economy, despite the huge financial help it has received, has not improved and actually appears sicker than ever. What explains this is a hard economic mechanism known as the Dutch Disease. 15 When the Netherlands discovered huge gas deposits in the 1960s it came very quickly to riches, which made it possible to raise wages faster than the productivity of its economy grew. This led to its industry losing part of its competitiveness, pushing the country into recession. It wasn't until the gas production slowed down that the wage-negotiating parties agreed on wage moderation, in what became known as the Wassenaar Agreement, bringing about a healing of the economy.

The situation in Greece today is similar to that in the Netherlands then, since whether a country sells gas or debt instruments to uphold an excessively high wage level makes no difference in terms of the effects on competitiveness. The more public credit is made available to a country, the longer its lack of competitiveness will last, irrespective of the reform conditions attached to the granting of credit. Only when public money ceases to be available, circumstances force through the painful wage and price adjustments needed to restore competitiveness.

A comparison between Ireland and the other crisis-stricken countries reinforces the above point. The Irish bubble burst already in late 2006, before any international rescue credit was available. The country, therefore, had to help itself. While elsewhere in the Eurozone massive wage increases were still being pushed through, Ireland reduced wage levels in the public and private sectors, triggering a reduction in prices as well. 16 Relative to the rest of the Eurozone, its goods prices (GDP deflator) sank by 13% between 2006 and 2013. Thanks to this “real devaluation”, the country became competitive once again and experienced a strong economic upturn. Irish GDP lay in the fourth quarter of 2014 9% higher than during the first quarter of 2010, while manufacturing output has jumped by 43% (first quarter 2015). 17

Such a development did not occur in the other crisis-affected countries because their crisis started only after Lehman, two years later than Ireland's, and opted for printing the money they could no longer borrow, a development discussed for Greece in Section 1. The financing of the current account and budget deficits with international public credit relieved the pressure to reform the economy and led to the necessary structural adjustments being relegated to the backburner, which is another manifestation of the Dutch Disease. While it is true that Ireland also participated in the rescue credits, most of its painful adjustment had by then already been completed.

This is well known in Greece as well. Former economics minister Michalis Chrysocoidis replied to a question in an interview with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung conducted in 2012 of whether the subsidies had destroyed Greece: "Yes. While we took the EU money with one hand, we did not invest that money with the other hand in new, competitive technologies. It all went to consumption. The result was that those who produced anything ceased to produce and decided to go into the import business, because the profits were higher. That is the real tragedy of the country." 18

Continue to Section 3: Who Benefited from the Rescue Credit?

Footnotes

1 See European Commission, European Economy, Occasional Papers 61, "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece", p. 25. The official estimate was based on the financing gap from May 2010 through June 2013 that was to be closed by the agreed help from the euro countries and the IMF (now labelled First Rescue Package). The credit was to be disbursed in single tranches contingent on the Greek financing needs. Slovakia refused to participate from the very beginning. After the second tranche, Ireland suspended payments and Portugal did likewise after the fourth tranche, because they themselves had to request financial help. This led to the fact that the first rescue package amounted to only 77.3 billion euros.

2 See A. Merkel: "The important thing is that with the rescue packages we have given the euro time for all countries to carry out the necessary budget consolidation – and, if necessary, to also carry out structural reforms." (Own translation.) See A. Merkel, "Merkel: Anstehende Aufgaben überzeugend umsetzen", N24 – Sommerinterview, 7 July 2010.

3 A. Merkel on 16 September 2010: "There won't be any extension of the current rescue package with Germany." (Own translation.) See H. Janssen, "Merkel und Schäuble in der Euro-Krise: Die Schönredner – Teil 2: 'Eine Verlängerung der jetzigen Rettungsschirme wird es mit Deutschland nicht geben'", Spiegel Online, 19 November 2012

4 Calculated as the average for January and February, since the value for March was not available at the time of writing.

5 See IMF, "Greece: Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access under the 2010 Stand-By Arrangement", IMF Country Report No. 13/156, June 2013, in particular p. 2, 21 and 33

6 See Spiegel Online, 23 March 2015. The sum of 958.77 euros cited by Spiegel Online and other news outlets for the average Greek pension comes from the Ministry of Labour in Athens. The average pension for German retirees amounts to 766 euros (734 euros in West Germany, 896 euros in East Germany). See Deutsche Rentenversicherung Bund, Rentenversicherung in Zeitreihen, October 2014, p. 201.

7 See S. Vogt, "Unter Druck – Griechenland im wirtschaftlichen, politischen und sozialen Reformprozess", KAS Auslandsinformationen 6, 2013; Zeit Online, "Griechenland scheitert an Umsetzung der Sparauflagen", 13 July 2012

8 See Handelsblatt, "Scharfe Kritik an Athener Steuerplänen", 23 March 2015; see also Hellenic Parliament, Legislative Work, Enacted Legislation, 20/03/2015, Regulations for the Restart of the Economy.

9 See Eurostat, Database, Population and Social Conditions, Labour Market, Employment and Unemployment. Earnings, Minimum Wages.

10 See Statistisches Bundesamt (German Federal Statistical Office), "EU-Vergleich der Arbeitskosten 2014: Deutschland auf Rang acht" Press Release No. 160, 4 May 2015.

11 See K. Hope and P. Spiegel, "Greece and Lenders Fall out over Firings", ft.com, 14 March 2013.

12 See European Commission, "The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, Fourth Review – April 2014", Occasional Papers 192, April 2014, p. 79ff.

13 See European Commission, "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, Fourth Review – Spring 2011", Occasional Papers 82, July 2011, p. 16.

14 See Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund, Asset Development Plan – December 2014. As to the historical process: the Troika corrected downward already back in October 2011 the cumulative proceeds of privatisation for the years 2011 through 2013. The goal of generating 50 billion euros through privatisation by the end of 2015, however, was maintained. See European Commission, "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, Fifth review - October 2011", Occasional Papers 87, 2011, p. 32. The Troika performed a further correction in 2012, expecting now proceeds of only 19 billion euros by the end of 2015. The report left the question open as to when the rest of the 50 billion could be expected. See European Commission, "The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, March 2012", Occasional Papers 94, 2012, p. 31. The Troika has meanwhile reduced its expectation of proceeds from privatisation until 2020 to 22.3 billion euros. See European Commission, "The Second Economic Adjustment Programme", op. cit., p. 27.

15 See N. M. Corden and J. P. Neary, "Booming Sector and De-Industrialization in a Small Open Economy", Economic Journal 92, 1982, p. 825–848.

16 See H.-W. Sinn, The Euro-Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets, and Beliefs, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, in particular Chapter 4: "The Competitiveness Problem", Section "How Did Ireland Do It?".

17 See Eurostat, Database, Economy and Finance, National Accounts (ESA 2010), Quarterly Accounts; same institution, Database, Industry, Trade and Services, Business Statistics, Industry. Figures for Irish GDP in the first quarter 2015 were not available at the time of this writing.

18 M. Chrysochoidis, "Die Gesellschaft ist reifer als ihr System", Interview by M. Martens, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 9 February 2012