The Greek Tragedy

7. Advantages and Disadvantages of a Grexit

Out of the four options outlined above, a Greek exit from the Eurozone and a return to the drachma may be the lesser evil, since the capital flight and the possible imposition of capital controls à la Cyprus would immediately cease if the currency were converted and the exchange rate left to float freely. The inevitable devaluation would attract fresh private capital. The lower the value of the drachma, the cheaper the Greek stocks and property, and the larger the number of investors, in particular wealthy Greeks who have absconded abroad, who would find it attractive to invest their funds in Greece. If private capital imports and exports balance each other out, a new equilibrium in the currency market would be achieved.

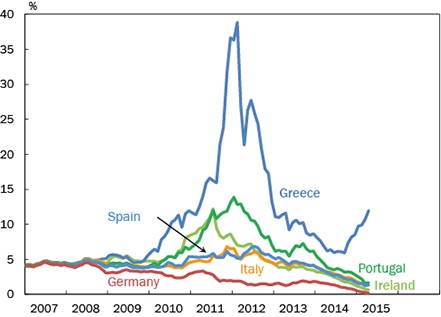

One argument put forth against a Grexit is that it would destabilise the euro, since other euro countries could become the object of speculation and would risk getting practically shot out of the common currency. While this risk cannot be simply waved away, the yields on the government bonds of the other crisis-afflicted countries tell a different story. As Figure 10 shows, they have all come down lately, while those on Greek government bonds have soared. Evidently, the markets do not see a particular risk of contagion. The Greek case has too many peculiarities for that.

Figure 10: Yields* on crisis-country and German government bonds

Click on image to enlarge*Effective interest rate for 10-year government bonds.

Source: Datastream.

The real risk is contagion at the political level if Greece does not leave the euro. As shown in Figure 1, Greece has received public credit amounting to 182% of its GDP. If such a level of help were to be given to the other crisis-afflicted countries, namely Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy, and Cyprus, whose combined GDP amounts to 3.05 trillion euros, the sum needed would be 5.5 trillion euros; in other words, a further 5.0 trillion euros would be needed on top of the help already provided to these countries. If we assume that 38% of this additional help, just as in the case of Greece, were given through the ECB and the rest through the ESM, Germany alone would have to shoulder around 1.6 trillion euros (almost 41% of the ECB help plus around 27% of the ESM help), which amounts to some 75% of its current public debt (2.17 trillion euros). Similarly, France would have to shoulder around 1.2 trillion euros or 61% of its current public debt (2.04 trillion euros). Such sums boggle the mind and could well push all of Europe into the abyss.

If, on the contrary, Greece were to exit, all parties involved would realise that help of comparable magnitude as that given to Greece is not on the cards, prompting them to redouble their reforming efforts – concretely, a policy of moderation and austerity – in order not to lurch into a situation such as Greece’s. That would usher in a process of disinflation, or even deflation, without which the necessary realignment of relative prices is not possible in the Eurozone. This insight will not arise out of statements and treaties, but solely through concrete action. How we react today to Greece's crisis will define the future of the European project. It is now that the decision will be made whether the Eurozone is to become a transfer and liability union in which parts of it will be on permanent support, succumbing thus to the Dutch Disease, or a currency union with well-functioning economies that are able to compete in the global arena because domestically they are competitive as well.

The political contagion effects resulting from a pooling of the investment risk à la Greece are huge, since such a pooling keeps the interest spreads low even when countries borrow excessively, because investors know that they will be rescued whenever danger looms. It also eliminates the natural debt brake that markets impose and lets the propensity to overborrow grow unhindered. This could be clearly observed in the years following the rescue operations of 2012, in particular after the announcement of the OMT programme by the ECB and the setting up of the permanent rescue fund ESM. The lowering of interest rates and the attendant relief for the government budget led to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio, despite the fact that the opposite had been agreed under the Fiscal Compact. The tendency to borrow can be so strong when risks are pooled that all moderation is lost, since the unitary European state and the power of a central government needed to keep this tendency in check is neither desired nor would it be tolerated by the peoples of Europe.

The ineffectiveness of mere treaties was amply demonstrated by the Stability and Growth Pact: its original rules were breached a hundred times and yet not once were the stipulated sanctions applied, because it was quickly and duly amended, and its stipulations grotesquely stretched. 1 The Fiscal Compact did not meet a better destiny. The Compact was pushed through by Germany as a precondition to its participation in the permanent rescue fund ESM. Under its tenets, every EU country, starting in 2013, was to reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio over a three-year period by an average of one-twentieth of its excess over the 60% ceiling. In practice, however, the debt-to-GDP ratio of all crisis-afflicted countries (except Ireland), as well as that of many other countries, continued to rise. By the end of 2011, when the Fiscal Compact was negotiated, the crisis countries’ average debt ratio amounted to 104.4% of GDP. Just three years later, by the end of 2014, it had risen to 121.8%. 2

The risk of Europe sliding ever deeper into a debt morass is far greater than that of a financial crisis. The current path can lead to national crises that are difficult to handle and which can cause rifts between the peoples of Europe. The painful experiences with debt mutualisation in the USA before its Civil War should serve as a warning that these risks should not be taken lightly, and that the calls for short-term alleviation voiced by the finance industry and the creditors should be resisted.

The first US finance minister, Alexander Hamilton, converted the state debts into federal debt in 1791 – in other words, he mutualised them – in order to "cement" the nascent union, as he said. Alas, it turned out to be anything but cement. The excessive borrowing triggered both by the initial mutualisation of debt as well as by a second one, prompted in 1813 by a second war against Britain, fed a credit bubble that burst in 1837. In the following five years, 9 out of 29 federal states and territories went bankrupt. Nothing but animosity and strife resulted from the mutualisation of debt. 3 As Harold James, an economic historian at Princeton, put it, Hamilton's cement turned out to be dynamite. He also sees a direct line from the burst of the bubble to the Civil War of 1861. While the Civil War was triggered by the slavery question, it was further fuelled by the unsolved debt problem. 4 It was not until after this war that the US introduced a regime of individual liability for the states, which has underpinned the stability of US federalism to this day.

Greece would reap both advantages and disadvantages from a return to the drachma. The obvious disadvantage would be that it could no longer issue money that is accepted as legal tender elsewhere. This would incidentally remove its main funding source of the past months.

Most of all, it would lack an instrument to put pressure on the international community to grant further fiscal credit. The fact that Greece has not set up capital controls to stop capital flight, opting instead for refinancing its commercial banks with ELA credit, can also be explained by the Greek government and the Greek central bank (and also the representatives of other countries in a similar situation) being intent on stoking a potential threat point in case the country exits the currency union. In case of an exit, the portion of the ELA credit and refinancing credit, which was made possible by lowering the collateral requirements that exceeded the local liquidity needs and became Target liabilities through the issuance of payment orders abroad, would presumably have to be written off, as discussed in Section 5. On the other hand, the assets that Greeks have acquired abroad with those funds would remain permanently in Greek hands and the foreign debt that Greek citizens have paid off with the money created in Greece would be permanently retired. The ECB, in contrast, would presumably have to write off its euro claims on the Greek central bank, which would go bankrupt, given that all its assets would be denominated in devalued drachmas. Since everyone knows this, the willingness of the international community to prevent an exit by providing new fiscal rescue credit increases the higher the Target liabilities and ELA credit rise.

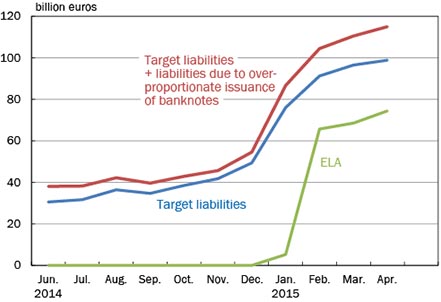

Since early 2015 until mid-May 2015, the Greek NCB has provided 80 billion in ELA credit to its commercial banks. Part of this sum has served to replace refinancing credit, the collateral for which was no longer being accepted by the ECB. Another portion served to offset the capital flight (as measured by the Target balances), as well as the cash withdrawals by Greek citizens who wanted to safeguard their wealth. Recently, the ELA credit volume has been rising by around one to two billion euros a week, and similarly is the sum of Greek Target liabilities and over-proportionate banknote issuance. And yet the two-third blocking majority to stop ELA credit has not been reached within the ECB Council.

Figure 11: Greek Target liabilities, over-proportionate banknote issuance and ELA credit

Click on image to enlargeSource: Bank of Greece, Financial Statements.

Not only the Greek government, but also those of the countries that have given Greece credit directly or through the ECB, can reap some benefits, if only cosmetic ones, if Greece remains in the Eurozone, even if it has to be propped up with further public credit. New rescue credit replaces the credit generated through money creation and brings down the Target balances, thus helping to mollify public opinion. Furthermore, the new rescue credit helps the finance ministries of the creditor nations by making it unnecessary to book immediately write-offs or write-downs of fiscal credit granted to Greece, which would impact the deficits, destroy the illusion of free-of-cost Greek rescues and unsettle the voters. The fact that further fiscal credit for Greece would lead to a dangerous long-term debt spiral would not unduly bother governments keen on re-election and successful PR.

But let us get back to Greek considerations. A tangible disadvantage of an exit is that imports will become more expensive due to a devaluation of the drachma, lowering the population's living standard. Shortfalls in medicines and energy could occur, forcing the international community to further rescue action.

The rise in import prices, however, is exactly what offers the right incentive to turn to domestic products, primarily from Greek farmers who have hitherto been priced out of the market by the high wages prevailing in Greece. Paradoxically, despite the competitive advantage offered by ideal weather and soil, Greece under the euro has become a net importer of agricultural products. Greek agricultural imports lay lately (2013) one-fourth above the corresponding exports. 5 The boost in demand resulting from a Grexit would make it attractive for farmers to hire more workers, whose wage income would go to buy more domestic products. It is even likely that it would revive the cotton industry, which used to provide work to farmers and textile workers and which was decimated by the higher wages in the wake of introduction of the euro.

On the positive side, an open currency devaluation would have a decisive advantage over a real devaluation performed through a lowering of wages and prices: it would avoid bankruptcies among debtors and tenants, since not only their income would be now denominated in drachmas but their liabilities as well. In other words, the balance sheets of companies and households would remain intact.

This advantage of course does not extend to those who have foreign debts. Since these debts are denominated in euros, the Greek debtors affected – companies, banks or the government – would find themselves in difficulties. They would, however, experience exactly the same difficulties if the devaluation were to come through a lowering of wages and prices. There is no difference.

To solve this problem, Greece's foreign creditors would probably have to once again, just as in 2012, waive part of their claims. But they must presumably do so in any case. The losses to the other member states calculated in Section 5 are largely independent of whether the Greek institutions go bankrupt inside or outside the Eurozone. The difference compared to 2012 is that Greece's creditors are now almost exclusively public institutions, including the ECB, since the private investors used the past five years to bring their money to safety.

It must be stressed that the problems of a haircut are not caused by a Greek devaluation, but because the country is insolvent. If anything, the losses to foreign creditors will diminish rather than increase in the wake of a devaluation, since although such a devaluation increases the value of the debt in relation to income and therefore causes immediate liquidity and balance-sheet problems, in the medium term it leads to an improvement in the Greek trade balance, which measures the real cash flow between the Greek economy and the rest of the world. Only when this cash flow improves, which is the equivalent of the primary surplus for the public budget, the Greek economy will be in a position to service at least part of its debt. This should be kept in mind by those who raise the foreign debt problem as an argument against a devaluation.

In view of the stronger competitiveness of the Greek economy and the relief of its debt problem resulting from an open devaluation, as compared to a real devaluation through wage and price cuts, the Greek population would likely benefit despite the dearer imports. In particular, the younger generation of Greeks, who have been pushed into unemployment by the real revaluation brought about by the euro (Fig. 2), would benefit from the revival of the labour market.

It is likely that the entire Greek economy would perk up after exiting the currency union. A study published in 2012 by the Ifo Institute, which examined some 70 countries that have defaulted during the post-war period and subsequently devalued their currency, found that in almost all cases after only one or two difficult years an upturn in the economy occurred. 6 The same was independently found by a recent Oxford Economics study that was much quoted in the press. 7

Even Argentina, which defaulted in 2001 and subsequently ditched its dollar peg, saw its economy flourish just two years after devaluing its currency, as the Ifo study shows, and grew steadily for an entire decade afterwards. The same occurred after the Asian crisis of the late 1990s, when several countries defaulted and then devalued their currencies. 8

Continue to Section 8: The Exit Procedure

Footnotes

1 See H.-W. Sinn, The Euro Trap. On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets, and Beliefs, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, Chapter 2, Section "The Lack of Fiscal Discipline".

2 See Eurostat, Press Release 62/2012, 23 April 2012 or Eurostat, Press Release 72/2015, 21 April 2015.

3 See H.-W. Sinn, op. cit., in particular Chapter 9, Section "Learning from the United States", as well as B. U. Ratchford, American State Debts, Duke University Press, Durham 1941.

4 See H. James, "Lessons for the Euro from History", Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy and Finance, 19 April 2012.

5 See World Trade Organization, Statistics database, Time series on international trade.

6 See B. Born, T. Buchen, K. Carstensen, C. Grimme, M. Kleemann, K. Wohlrabe, T. Wollmershäuser, "Austritt Griechenlands aus der Europäischen Währungsunion: Historische Erfahrungen, makroökonomische Konsequenzen und organisatorische Umsetzung", ifo Schnelldienst 65, 10, p. 9-37.

7 Cf. "Lehren für Griechenland aus dem Scheitern von 70 Währungsunionen", Welt Online, 13 May 2015.

8 See Born, Buchen et al., op. cit. and similarly, R. Fernández and J. Portes, "Argentina's Lessons for Greece", Project Syndicate, 9 February 2015.