Europe, the Swiss Way

National and cultural identities currently play a prominent role in European policy debates. This is a worrisome development for the European Union, an institutional process meant to remove not only the economic, but also the cultural and political boundaries of nations that have historically built consensus around centralised institutions through cultural assimilation, and have engaged in approximately two major intra-European wars per century.

Many who hope that Europe will develop a more cohesive political structure are fond of de Rougemont’s (1965) picture of Swiss federalism. Switzerland, in fact, reminds Europeans of the distant past before nations were formed, when the Holy Roman Emperor decided that the rural valleys around the Gotthard pass would be subordinate only to his central authority, and populated by free men rather than by serfs tied by feudal obligations to the land and to a religious or lay local lord. EEAG (2014) review the origins and recent evolution of the Swiss Confederation’s socio-political configuration, and argue that some of its features may be adapted for use in the European Union.

A different flavour of EuropeSwitzerland largely refrained from engaging in the nation-building phase of European history and long maintained a fiscally decentralised and traditional type of socio-economic organisation, similar to that which prevailed throughout Europe before the Industrial Revolution. The Swiss Confederation still allows different cultures and fiercely independent political entities to coexist within its boundaries, has only slowly integrated its internal economic and institutional structure, and has not taken part in the European unification project that is challenged by the current crisis.

Switzerland’s history and current policy issues, however, are deeply connected with those of its European neighbours. Switzerland remained neutral in Europe’s frequent wars, but its internal cohesion was fostered by the need to defend itself from aggression. Moreover, it is currently facing many of the policy problems that trouble its European neighbours. In the past two decades, Switzerland has developed an internal common market linked to the European Union’s, it has introduced federal social insurance schemes that are approaching the size and unsustainability typical of continental European nations, and pioneered “debt brake” public budget rules. It is concerned about immigration, and the latest referendum outcome displays a worrying turn away from the principles of an internationally open liberal economy.

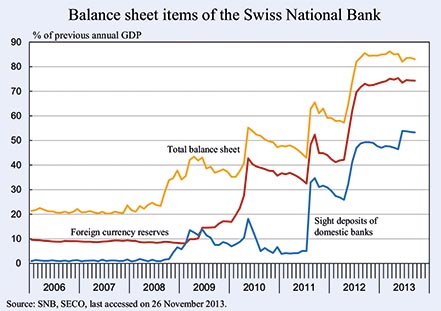

CrisisRecently, the Swiss have faced financial and monetary crises similar to those that threaten to break up the euro area. They had to bail out a very large bank. Furthermore, to prevent portfolio-driven currency movements from disrupting its economy, the Swiss Central Bank bravely accumulated foreign exchange reserves (see Figure 1) that, in proportion to GDP, exceed the TARGET2 balances that arose for similar reasons within the Eurosystem (Cour-Thimann, 2013) and generated a great deal of concern (Sinn, 2012 and 2014).

Figure 1:Click on image to enlarge

Cohesion

The intensity and character of the crisis in Switzerland have not been significantly different from the rest of Europe. However, Swiss policy reactions have arguably been more effective, and certainly less controversial, than those of the European Union and of its member countries.

To understand why the tensions that currently threaten to derail Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union are largely absent in Switzerland, one needs to consider how the country’s institutional structure is shaped by its deep internal cultural heterogeneity. This may, in fact, be the key factor explaining not only Switzerland’s proverbial stability (Kirchgaessner, 2013), but also its ability to devise and implement pragmatic and democratic solutions to policy problems.

In Switzerland, cooperation is rooted in the “Konkordanz” principle of compromise between heterogeneous special interests and decentralised decision powers. This principle was developed after the 1848 civil war to manage the peaceful coexistence of cultures ranging from the Germanic, Catholic, rural, and conservative cultures of the original Cantons, to the Protestant, Romanic, and enlightened culture of Geneva, and encompassing a large variety of local cultural specificities.

Managing diversityNation states traditionally root cooperation, solidarity, and market integration in processes of cultural assimilation. This approach is extremely difficult to apply at the European level, as shown not only by the failure of past French and German attempts to engineer continent-wide versions of their own nations’ conquest-based origins, but also by the very mixed success of the European Union elites’ top-down approach to supranational policy-making, which has proved unable to tackle the most politically important social and fiscal aspects of policy.

Swiss history suggests that cooperation and trade across culturally different societies is neither easy nor riskless, but certainly possible and fruitful. Cultural heterogeneity is widespread and multi-dimensional in Switzerland, and while socio-political relations are very frequently local, the borders across languages, religions, and traditional versus progressive cultures do not overlap perfectly.

Hence, Swiss society is not segmented into the homogeneous sets of humanity that national states would like to form. When each individual belongs to several of a multitude of communities, it is natural for power to be dispersed and for decisions to be collegially shared in the typically Swiss “Konkordanzdemokratie” political model.

And diversity does not need to be eradicated when public policies and institutions recognise it explicitly, and durable compromises addressing common problems are cemented by the self-enforcing realisation that breaking agreements in pursuit of immediate gains would entail larger losses.

Lessons for EuropeSwitzerland is becoming more similar to its European neighbours in various ways, and more tightly integrated with their financial, fiscal, and market structure. Europe’s policy-making framework may, in turn, stand to benefit from becoming more Swiss in its approach to conflicts of interest arising from dimensions that are not necessarily geographically or ethnically local.

When compromises between the economic advantages and policy disadvantages of diversity cannot rely on the coincidence of geographical, cultural, and political boundaries, the well-respected pragmatic rules of Switzerland are better than the vaguely enforced and ideological rules of Nationalistic cultures.

The European Union would do well to draw inspiration from the Swiss. Its institutional features should be looser and less centralised than in traditional nation states, but clearly focused on the administrative, legal, monetary, and fiscal instruments that support market relationships. Moreover, like in Switzerland, its diverse cultures should be held together by the common foreign policy and shared external concerns that may become urgent if the evolution of the world’s geo-political configuration makes it necessary for Europe to assert its common interests without the support of the United States.

Giuseppe Bertola, Harold James, and Jan-Egbert Sturm

This column is based on EEAG (2014), The EEAG Report on the European Economy, “Switzerland: Relic of the Past, Model for the Future?,” CESifo, Munich 2014, pp. 55-73 (http://www.cesifo.org/eeag). The EEAG members are Akos Valentinyi (Cardiff Business School, Chairman), Giuseppe Bertola (EDHEC Business School), John Driffill (Birkbeck College), Harold James (Princeton University), Hans-Werner Sinn (Ifo Institute and LMU University of Munich) and Jan-Egbert Sturm (KOF Swiss Economic Institute, ETH Zurich). They are collectively responsible for each chapter in the report. They participate on a personal basis and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisations they are affiliated with.

ReferencesCour-Thimann, P. (2013), “Target Balances and the Crisis in the Euro Area,” CESifo Forum 14, Special Issue.

de Rougemont, Denis (1965), La Suisse ou l'Histoire d'un Peuple Heureux, reedited, l’Age d’Homme, Lausanne 1990.

EEAG (2014), The EEAG Report on the European Economy, “Switzerland: Relic of the Past, Model for the Future?,” CESifo, Munich 2014, pp. 55–73.

Kirchgaessner, G. (2013), “Consociational Democracy, Divided Government, and the Possibility of Reforms,” in: Z.T. Pallinger, ed., Political Crisis in Europe: Direct Democratic Answers, VS Verlag fuer Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden.

Sinn, H.-W. (2012), Die Target-Falle. Gefahren für unser Geld und unsere Kinder, Hanser, Munich.

Sinn, H.-W. (2014), The Euro Trap: On Bursting Bubbles, Budgets and Beliefs, Oxford University Press, forthcoming.