Banking union: could it turn out better than expected?

The EU’s proposals for a banking union have made surprising progress, despite widespread scepticism and opposition from some influential quarters. The newspapers have ridiculed the EU’s Baroque procedures for deciding how to resolve a failing bank (numerous bloated committees involving well over a hundred people) and its tiny fig-leaf of a fund to pay for the costs of resolution (only 55 billion euros, less than a month’s Federal Reserve spending on Quantitative Easing, and that only after a ten-year build-up period). Bathed in the bland pieties of euro-speak, Europe’s lofty ambitions are hard to take at face value. While the Commission’s assertion that: “Swift progress towards a banking union is indispensable to ensure financial stability and growth in the euro area and in the whole single market” may be true, such statements cover a multitude of sins. How often have we been here before? Previous schemes with lofty ambitions – the Euro, for example – have had spectacularly unexpected consequences. How will the banking union concept turn out in practice?

Exposing the legacy problemsThe Commission and the Council of the EU agreed on a scheme for a Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) and a Single Bank Resolution Fund (SRF) on 18 December 2013, with only a few details left to be worked out (although one of them is the crucial detail of the backstop to the SRF), and needing only to reach an agreement with the European Parliament. The Single Supervisory Mechanism is in place; the European Central Bank (ECB) is set to take over as the ultimate supervisor and regulator of all euro area banks in November 2014, and is conducting its comprehensive assessment of asset quality and balance sheets of the roughly 130 largest and systemically most important banks to root out any legacy problems prior to that point. Acharya and Steffen (2014) have examined the publicly available data on these banks’ balance sheets and ask what the findings of the comprehensive assessment might be, and how much additional capital the banks may need. One of their more eye-catching estimates is that there might be a capital shortfall of 579 billion euros in a systemic crisis. This sounds like a huge figure. It is 18.2 times the market value of the banks’ equity and 1.5 times the value of equity plus subordinated debt. Given that other forms of debt are largely exempt from bail-in on current proposals, substantial losses for taxpayers seem possible. The banking systems of Belgium, Greece and Cyprus, in particular, are likely to need public support.

One of the dangers is that the ECB will recoil from openly exposing such large shortfalls and will insist on getting bank capital shored up by this amount, because it would add to the burdens on fragile member states in the short term, despite its improving longer-term stability. But this would be a very discouraging omen. In such a scenario banking union may turn out to be a device for channelling resources to periphery member states, by mutualising banks’ write-off losses on the holdings of legacy debt of near bankrupt states and dubious real-estate projects across the euro area. The ECB is the largest creditor of the endangered banks and has accepted large amounts of below-investment grade assets as collateral, issuing nearly 80 percent of the Eurosystem's monetary base via the banks of the six crisis-afflicted countries: Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Cyprus, which account for just a third of the euro countries' GDP. In view of its own precarious exposure, the ECB may therefore be tempted to seek resolution methods that shift the burden of write-off losses onto the taxpayers of the still-solvent euro area member states. This is an aspect that makes us wonder whether it was a wise decision to place the SRM in the hands of the ECB.

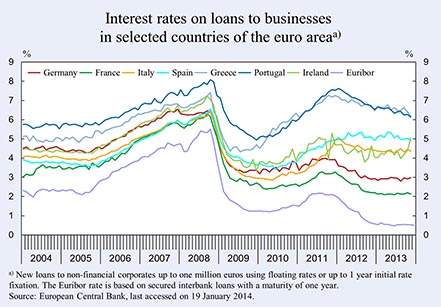

The single market in financial servicesOne of the stated aims of the banking union is to narrow the differences between euro area member states in the cost of financing for households and small firms, which have widened, as ECB data in Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1: Click on image to enlarge

The ECB argues that its monetary policy is not transmitted effectively to the periphery because of the linkages between fragile states and fragile banking systems; high borrowing costs in the periphery are choking off recovery and prolonging the debt crisis. The banking union is intended to address this issue. If there was a fully effective single market in financial services, maintains the ECB, borrowing costs would depend only on the risks of the loan in question, and not at all on the default risk of the government of the country in which the borrower was located. Unfortunately, this view is unconvincing, as it implicitly assumes that member states have already been dissolved into a European federal state. In the absence of a European federal state, each euro area member state, its banks, households and enterprises are bound together, sharing the same idiosyncratic country risks, through that member state’s taxes, regulations and responsibilities. A policy that completely removed country-specific interest spreads in such a situation would lead to a misallocation of resources, as it would neglect differences in national repayment probabilities and the probabilities of euro exits. The borrowing cost differentials observed since 2009 clearly reflect the tendency of markets to distinguish between borrowers by repayment probability, reversing the tendency before the crisis to lend recklessly, ignoring these risks. A banking union may reduce, but is unlikely to eliminate these differences in borrowing costs; and indeed it should not do so.

The bank-sovereign nexusDuring the crisis, the banks and sovereigns of the euro periphery developed even closer ties than prior to it, as banks were allowed to borrow money from the local printing presses of the national central banks to buy government bonds and use these government bonds as collateral, even though rating agencies had declared them non-investment grade. The states, in turn, protected their banks with implicit and explicit rescue promises encouraging them to buy government bonds. In Ireland these promises, which went far beyond protecting the deposits, led to huge obligations of the state, forcing it to borrow to recapitalise the banks. As we argue in the 2014 EEAG Report on the European Economy (EEAG, 2014), the link between banks and governments was also strengthened by the EU's interpretation of the Basel agreement on banking regulation, allowing banks to load their balance sheets with government bonds without having to hold equity against them, although the banks’ own risk models would have made that necessary. Thus, the toxic link that some EU politicians now want to cut by distributing some of the risk of write-off losses among the taxpayers and banks of other countries largely results from their own prior policy mistakes.

The future financial stability of the euro area will depend only partly on the banking union. It will, however, depend heavily on member states lowering their fiscal deficits and restoring sound public finances, reducing the supply of public debt and increasing wider market demand for it. It will also depend on the imposition of sensible risk weights under Basel III, which better reflect the true default risks on public debt, and on the generally tighter regulation of banking. The concept of a banking union is only one feature in a larger landscape of reform.

Bail-inA banking union will usefully discourage banks from holding excessive amounts of public debt through the design of the bail-in tool, which is a key plank in the SRM. It requires that banks structure their liabilities (deposits, equity, and debt) so that they can be bailed in at an amount equal to at least eight percent of their liabilities and own funds should they get into difficulties. This is intended to induce creditors to monitor banks more carefully, to encourage the banks to hold less risky asset portfolios, and to lower the cost of bank resolution borne by taxpayers. However, the usefulness of the bail-in tool is limited by a long list of exemptions. Moreover, eight percent of the balance sheet sounds tiny for truly zombie banks, raising the question: who will stand in for the other 92 percent if necessary? Thus the bail-in tool may be more window dressing than reality. The Commission proposals spell out that banks will not be allowed to structure their liabilities so as to avoid it (EEAG, 2014), but concrete proposals for guaranteeing a certain fraction of bailable liabilities have been blocked by France to date.

ConclusionAt this stage a nearly complete set of proposals for a banking union has been set out, but we do not yet know how they will work out in practice. There are clearly some dangers: that the ECB will not be the fearless, impartial supervisor desired; that conflicts between monetary and financial stability, and concerns about its own balance sheet, burdened with periphery public debt, will lead it to practice excessive regulatory forbearance. The results of the comprehensive assessment later in 2014 will be a vital signal in this respect.

The merits of the bail-in tool depend on the perspective from which it is judged. If the benchmark is a situation whereby taxpayers are responsible for meeting the banks' write-off losses, bail-in sounds like a protective device for taxpayers. However, when the benchmark is a situation whereby the banks’ creditors bear the consequences of their mis-investments, the Commission proposals sound more like rules for an organised bail-out than anything else. Final judgment on the banking union will therefore depend on how much taxpayers’ money, coming from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), will eventually be used to close the foreseeable financing gap in bank balance sheets. Using ESM money will relax the problematic link between banks and sovereigns in the short term, but will create incentives to strengthen them in the long run.

John Driffill and Hans-Werner Sinn

This column is based on EEAG (2014), The EEAG Report on the European Economy, “Banking Union: Who Should Take Charge?,” CESifo, Munich 2014, pp. 91-108. The EEAG members are Akos Valentinyi (Cardiff Business School, Chairman), Giuseppe Bertola (EDHEC Business School), John Driffill (Birkbeck College), Harold James (Princeton University), Hans-Werner Sinn (Ifo Institute and LMU University of Munich) and Jan-Egbert Sturm (KOF Swiss Economic Institute, ETH Zurich). They are collectively responsible for each chapter in the report. They participate on a personal basis and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisations they are affiliated with.

References

Acharya, V. V. and S. Steffen (2014), “Falling Short of Expectations? Stress-testing the European Banking System,” VoxEU, 17 January.

EEAG (2014), The EEAG Report on the European Economy 2014, “Banking Union: Who Should Take Charge,” CESifo, Munich 2014, pp. 91–108.